Multiplication theorem

In mathematics, the multiplication theorem is a certain type of identity obeyed by many special functions related to the gamma function. For the explicit case of the gamma function, the identity is a product of values; thus the name. The various relations all stem from the same underlying principle; that is, the relation for one special function can be derived from that for the others, and is simply a manifestation of the same identity in different guises.

Contents |

Finite characteristic

The multiplication theorem takes two common forms. In the first case, a finite number of terms are added or multiplied to give the relation. In the second case, an infinite number of terms are added or multiplied. The finite form typically occurs only for the gamma and related functions, for which the identity follows from a p-adic relation over a finite field. For example, the multiplication theorem for the gamma function follows from the Chowla–Selberg formula, which follows from the theory of complex multiplication. The infinite sums are much more common, and follow from characteristic zero relations on the hypergeometric series.

The following tabulates the various appearances of the multiplication theorem for finite characteristic; the characteristic zero relations are given further down. In all cases, n and k are non-negative integers. For the special case of n = 2, the theorem is commonly referred to as the duplication formula.

Gamma function

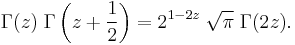

The duplication formula and the multiplication theorem for the gamma function are the prototypical examples. The duplication formula for the gamma function is

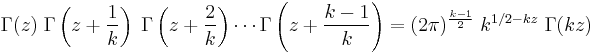

It is sometimes called the Legendre duplication formula[1] or Legendre relation, in honor of Adrien-Marie Legendre. The multiplication theorem is

for integer k ≥ 1, and is sometimes called Gauss's multiplication formula, in honour of Carl Friedrich Gauss. The multiplication theorem for the gamma functions can be understood to be a special case, for the trivial character, of the Chowla–Selberg formula.

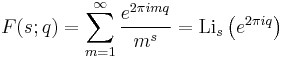

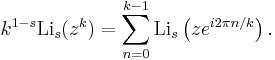

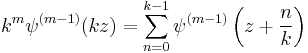

Polygamma function

The polygamma function is the logarithmic derivative of the gamma function, and thus, the multiplication theorem becomes additive, instead of multiplicative:

for  , and, for

, and, for  , one has the digamma function:

, one has the digamma function:

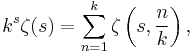

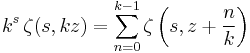

Hurwitz zeta function

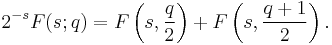

For the Hurwitz zeta function generalizes the polygamma function to non-integer orders, and thus obeys a very similar multiplication theorem:

where  is the Riemann zeta function. This is a special case of

is the Riemann zeta function. This is a special case of

and

Multiplication formulas for the non-principal characters may be given in the form of Dirichlet L-functions.

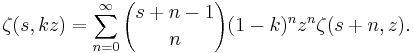

Periodic zeta function

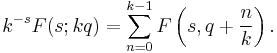

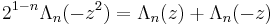

The periodic zeta function[2] is sometimes defined as

where Lis(z) is the polylogarithm. It obeys the duplication formula

As such, it is an eigenvector of the Bernoulli operator with eigenvalue 2−s. The multiplication theorem is

The periodic zeta function occurs in the reflection formula for the Hurwitz zeta function, which is why the relation that it obeys, and the Hurwitz zeta relation, differ by the interchange of s → −s.

The Bernoulli polynomials may be obtained as a limiting case of the periodic zeta function, taking s to be an integer, and thus the multiplication theorem there can be derived from the above. Similarly, substituting q = log z leads to the multiplication theorem for the polylogarithm.

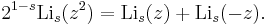

Polylogarithm

The duplication formula takes the form

The general multiplication formula is in the form of a Gauss sum or discrete Fourier transform:

These identities follow from that on the periodic zeta function, taking z = log q.

Kummer's function

The duplication formula for Kummer's function is

and thus resembles that for the polylogarithm, but twisted by i.

Bernoulli polynomials

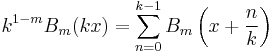

For the Bernoulli polynomials, the multiplication theorems were given by Joseph Ludwig Raabe in 1851:

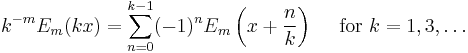

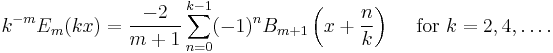

and for the Euler polynomials,

and

The Bernoulli polynomials may be obtained as a special case of the Hurwitz zeta function, and thus the identities follow from there.

Characteristic zero

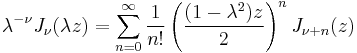

The multiplication theorem over a field of characteristic zero does not close after a finite number of terms, but requires an infinite series to be expressed. Examples include that for the Bessel function  :

:

where  and

and  may be taken as arbitrary complex numbers. Such characteristic-zero identities follow generally from one of many possible identities on the hypergeometric series.

may be taken as arbitrary complex numbers. Such characteristic-zero identities follow generally from one of many possible identities on the hypergeometric series.

Notes

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W., "Legendre Duplication Formula" from MathWorld.

- ^ Apostol, Introduction to analytic number theory, Springer

References

- Milton Abramowitz and Irene A. Stegun, eds. Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables, (1972) Dover, New York. (Multiplication theorems are individually listed chapter by chapter)

- C. Truesdell, "On the Addition and Multiplication Theorems for the Special Functions", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Mathematics, (1950) pp.752–757.

![k\left[\psi(kz)-\log(k)\right] = \sum_{n=0}^{k-1}

\psi\left(z%2B\frac{n}{k}\right).](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/09f6721e11886889efb0a091681ab90d.png)